Winter lung

Higher altitudes dudes (and dudette’s)

The winter months, and the long invitation to be up in the alps, touring, snowboarding, and all sorts of mountaineering bring about some epic times for all. It’s great to know that we are capable of such mean feats of ice climbing, aerial acrobatics, and intense high altitude fitness such as in cross-country ski touring.

Here I discuss a couple of the main challenges we have in respect to lungs/airways, and a little bit of insight into the neat acclimatisation processes our body undergoes at altitude.

Up here, where I sit on top of the Whakatipu basins largest peak, the Remarkables mountain range, so called because it is one of only two mountain ranges in the world that run directly North to South, I am at approx 1600m elevation, with the option to climb up above 2300m where some of the wilder powder cliff drops and snow runs sit.

The colder air, at altitude also comes with a dryness. Our main challenge with this, is keeping the mucosal linings of the airways and lungs from drying out, as often the mucosa is drying faster than it can be replenished. The airway lining then becomes hypertonic (increased tone/tightness), which can be counteracted by nasal breathing, kind of difficult if your ploughing your way down the hill at speed or cross-country touring. Consuming enough water, and limiting diuretics like caffeine is useful in preventing drying out. The dryness can also make us susceptible to infection as the mucosal layer usually acts as a penetration barrier to invading pathogens.

The Whakatipu basin area, whilst notoriously dry and lacking in a substantiating source of native foods, was a nice place for the Maori to heal, as identified by being known for having their sick and elderly whanau members there across the summer months. Recuperating a chesty, pneumonia driven cough, easily picked up in the other parts of New Zealands wet areas, would be easier in the warmer dry climate, surrounded by mineralised glacial waters.

These days, with the inevitable draw for the avid mountaineers to winter sports, the colder air exposure can also make our airway lining release pro-inflammatory substances, which is involved in the control of bronchial blood flow, and the vasodilation of bronchial vessels (which can thicken the mucosa).

This can make our airways a little more responsive, not too much of a problem, unless you already have an issue such as asthma and these inflammatory substances are elevated already.

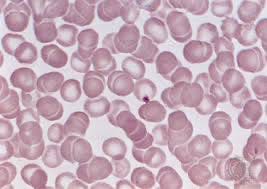

Apart from this challenge, the best part about spending time at altitude is the natural “blood doping” (it’s not really doping). Whereby the blood gets thicker, in response to the low oxygen partial pressures.

The physiology -

Discovered in the 1990’s, HIF‐1α, a protein in the body that was difficult to find because of how quickly it breaks down in the body in normal sea level conditions, is responsible for binding the EPO gene on chromosome 7 in low oxygen conditions. EPO (endogenous erythropoietin) is made by the body in the kidneys (and smaller amounts in liver, spleen, bone marrow, brain and lung).

At 1900m, this correlates with 30% increase in EPO

At 4500m, this correlates with a 300% increase in EPO.

EPO binds to the erythroid cells in bone marrow, triggering an increase in iron turnover, and a doubling of Red Blood Cells with a nucleus, in just 7 days. That thickens the blood considerably. Good if your healthy as your now able to carry a lot more oxygen, not good if the fast food has given you blood clots and fatty organs….

The effects of having increased your red blood cells can last for some time after descending from altitude, a neat little trick if your into enhancing your fitness and health. A review of the data, shows approximately a 50% reduction in the total haemoglobin count, in 3 weeks after return to sea level, however, don’t go thinking to return and run straight into a race at peak performance, as that first week on return has been noted for poor performance when studying athletes, why? I’m not sure, maybe the bloods a bit thick still, or otherwise factors of acclimatising to the rapid change in climate.

The body also has an incredible way of making you more efficient at carrying and distributing oxygen by shifting the plasma and water in the body to different places, a process less studied and understood.

So main points are

At altitude keep hydrated, and nose breath whenever you can

Don’t eat to heavy like thick cheese or fatty when your up the mountain as your blood might be too thick (stress on the heart etc and risk of clots)

Training at altitude may increase your ability to carry oxygen in the blood, is better the higher you area, and can last for a few weeks after the descent

Pre-existing airway issues can become problematic as your body seeks to adjust to the cold, dry air.